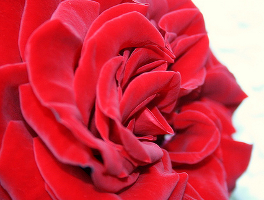

Amy Stewart’s wonderful book on the cut flower industry, Flower Confidential, begins with a conversation about scent:

“What’s the first thing a person does when you hand them flowers?” Bob Otsuka, general manager of the San Francisco Flower Mart, asked me. To answer his own question, he pantomimed the gesture people make, bringing his hands to his face and breathing deeply.

“They smell them,” he said. (p. 1)

But fragrance, as we know so well, is expensive. It costs plants a lot of energy to produce, and it shortens the lives of their blooms. Cut flowers, like those sold at the Flower Mart, are “bred for industry” — for color, uniformity, and durability. Along the way, most have lost their scent.

And yet, Otsuka tells Stewart, “People still want to believe that flowers smell good. I’ve seen somebody put their face right into a bunch of ‘Leonides’ and say, ‘Oh, they smell wonderful.’ But I know that rose. It’s got gold petals with coppery edges — you know the one I mean? It was bred for fall weddings. And it doesn’t have any fragrance at all.” (Ibid.)

Stewart goes on to see many floral marvels, but the story of those scentless roses haunts the rest of the book. It’s a small parable on the perils of turning the beauty and romance of flowers into a very big business, and a poignant reminder of the way we instinctively use our sense of smell to connect to the world. Later, Stewart catches herself sniffing at a bouquet even though she knows there is nothing to smell.

I’ve thought of those scentless roses often, and wistfully. So this May, when the large UK-based flower seller Interflora (a division of FTD) announced they would be showing four new fragrant rose bouquets at the Chelsea Flower Show I paid attention…