"The Art of Scent 1889-2012," the first exhibition organized by the Department of Olfactory Art at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, opened to the public on November 20. According to the press release, this exhibition, curated by Chandler Burr, "examines major stylistic developments in the evolution and design of fragrance, and provides unprecedented insight into the creative visions and intricate processes of the artists responsible for crafting the featured works." I've attended the exhibition twice over the past few days, and my reactions are mixed and complicated; I'll try to summarize them here, along with a few photos I've taken.

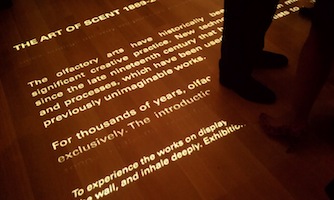

"The Art of Scent" is installed in the Museum's fourth-floor galleries, in a spare, neutral space created by the design firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The main gallery's matte white walls are punctuated by twelve curved recesses. From a distance, these niches resemble high-concept urinals or drinking fountains; upon closer inspection, they also suggest certain anatomical forms. Each recess houses a "scent machine" that releases a fine stream of fragranced air when its motion sensor is triggered. The accompanying "labels" are projections that fade in and out of view at timed intervals. (It's a slightly annoying effect if you're waiting for a text to appear or if it vanishes while you're reading it).

I won't keep you in suspense any longer: the twelve featured fragrances are Guerlain Jicky (Romanticism); Chanel No. 5 (Modernism); Givenchy L'Interdit (Abstract Expressionism); Clinique Aromatics Elixir (Early American School); Drakkar Noir (Industrialism); Thierry Mugler Angel (Surrealism); Issey Miyake L'Eau d'Issey (Minimalism); Estée Lauder Pleasures (Photo Realism); Dolce & Gabbana Light Blue (Kinetic Sculpture); Prada Amber (Neo-Romanticism); Hermès Osmanthe Yunnan (Luminism); and Maison Martin Margiela Untitled (Post-Brutalism).

If you're a regular reader of Burr's work, you won't find many surprises on that list; he has written about most of these fragrances elsewhere and has included several of them in his "scent dinners." We could argue back and forth over the inclusion or exclusion of certain perfumes; in any case, a third of the twelve were created after 2000, and there's nothing from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1960s, and only one from the 1950s, L'Interdit (which has been reformulated more than once since 1957).

We could also spend a while debating the thorny issue of sponsorship. In the gallery, a wall text beside the elevator lists the exhibition's "Major Donors" and other financial supporters. Eleven of the twelve featured fragrances, by my count, have connections to the brands and laboratories that have financed the exhibition. Of course, only giant, multi-national companies would be able to supply the necessary materials for this kind of installation. It's the kind of Catch-22 situation that affects anyone who's planning an exhibition of work by living artists or designers and the institutions that represent them; all the same, the high level of donor involvement here made me a bit uneasy.

Instead, I'll try to focus on two other issues: the information we're given within the space of the show, and the information we aren't given. The labels for the older fragrances offer straightforward, if abbreviated, historical background with an emphasis on raw materials. The further we advance along the timeline, the vaguer the labels become: a fragrance "inspires a mixture of excitement and unease" or "seems at once everywhere and nowhere"; a perfumer "reconceptualize[s] the medium of scent." I understand the challenge of museum labels, which need to compress months or years of research into a hundred words — I've written more than a few such labels myself — but I wanted more from these texts. They felt oddly myopic to me. The label text for Light Blue, curiously enough, makes no mention of Dolce & Gabbana; the discussion of Osmanthe Yunnan does not refer to osmanthus or to Yunnan.

The "Art of Scent" press release makes the point that this exhibition showcases the fragrances themselves, "through the near-complete removal of visual indicators, such as logos and marketing materials, encouraging visitors to concentrate exclusively on the sense of smell." To me, the problem with focusing only on materials, technique, and technology is that the fragrances are divorced from the complex webs of commerce and fashion and social history and use that surround them.

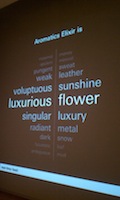

During both my visits, the second, smaller room of "The Art of Scent" seemed to be holding museum-goers' interest longer than the main gallery. This space is less didactic and more interactive. A long table is set with small glass bowls containing the fragrances in their usual liquid form, and visitors are encouraged to dip a paper blotter into a fragrance, then to select words to describe it from an iPad's touch-screen menu of nouns and adjectives. The accrued results for each fragrance are projected on the wall in "real time."

Along another wall of this gallery, we are introduced to the process of honing a fragrance's formula, through the participation of perfumer Sophia Grojsman: a row of five dispensers (again, disturbingly anatomical) offers cardboard squares scented with Lancôme Trésor in five stages of its development, each explained in a few lines by the Grojsman. And on the facing wall, a video monitor shows short interviews with four perfumers. I couldn't help noticing that, instead of dwelling on materials and techniques, every one of them spoke about the importance of smell — all kinds of smells — in their early memories and personal histories. This attitude seems strangely (but pleasantly) at odds with the somewhat antiseptic presentation of the first room.

My mind also keeps coming back to the parallels that this project draws between the twelve fragrances and specific movements or schools in art history (see list above). I don't believe that we can necessarily draw direct analogies between art forms, even within the same decade. Various mediums of art and design don't march in lockstep. I could write a few hundred words more on the inaccuracies of describing L'Interdit as a work of Abstract Expressionism, or on the anachronistic use of the term Luminism (with a capital "L") to describe Osmanthe Yunnan. Why visual art, anyway? If we must have this kind of comparison, why not architecture, dance, literature? And doesn't fragrance have its own schools, its own traditions, waiting to be named?

But let's say we do adopt art historical methodologies to interpret fragrance: no work of art (visual or otherwise) is created in a vacuum. If I heard someone lecture about Fra Angelico's use of perspective in a Renaissance altarpiece without discussing the work's original setting, religious symbolism, or historically significant patron, I'd feel cheated of a full understanding of the object. If I lectured about the bravura brushwork in a John Singer Sargent portrait but never discussed the conventions of Western portraiture or the portrait's subjects and their way of living, my listeners would be left with unanswered questions. If a conservator bombarded me with the chemical names for pigments used in a specific painting, I'd need to know how they translate into blues, reds, and browns; the scientific terminology alone wouldn't hold much initial meaning for me.

When we see a brand name on a perfume bottle, we do bring preconceptions and associations to the fragrance inside, but that dynamic runs in more than one direction: the client has commissioned a fragrance that suits its overall image. When everything comes together as it should, there's a correlation between the fragrance and the surrounding aesthetic of the designer and/or brand, to say nothing of the cultural moment in which the fragrance was created. Can Angel really cast its full spell without the imagery of its star-shaped bottle and Mugler's futuristic, wasp-waisted glamazons? Can we consider L'Eau d'Issey without knowing something about Miyake's monochromatic garments, with their radically simplified yet versatile designs? What about the innovative jersey suits and little black dresses also sold by Chanel in the 1920s, to say nothing of women's changing societal roles during that era? And exactly why have "clean" and "fresh" fragrances been so popular over the past two decades?

The actual exhibition of "The Art of Scent" isn't the end of the story: it will be accompanied by a catalogue packaged with small bottles of each fragrance (available for pre-sale, $250) and a series of lectures and workshops (most already sold-out). As a stand-alone event, however, the exhibition disappoints me somewhat. I love fragrance. I'm very fond of the Museum of Arts and Design. I'll look forward to learning about the Department of Olfactory Art's upcoming projects and — I hope — to seeing the art of fragrance presented in a wider range of interpretations.

"The Art of Scent 1889-2012" remains open through February 24, 2013. The Museum of Arts and Design is located at 2 Columbus Circle in New York; for more information, visit the museum website.

All photographs courtesy of the author. Bonus for anyone who has read this far: the man reading the label for Angel is rock legend Lou Reed, at the exhibition opening.

Many thanks for such a thoughtful and careful review. I at last feel I have a grasp of the exhibition’s intent, and kno what the hype has been about.

I share your qualms about an exhibition that divorces fragrance from the context of its production and use. Context is everything. (A further analogy, apart from those you mention, is literary scholarship that studies texts and authors but not how texts are transmitted via actual books to actual readers. And there would be a further example in the history of photography … )

It’s also interesting that the exhibition labels get more abstract and less meaningful as the exhibition goes on. I wonder what is going on there? Is the curator’s response to fragrances created in his own lifetime becoming more expressive, or personal, as the show goes on? It is indeed hard to write those labels but usually you aim for consistency of interpretation across them all.

I’m so glad you mentioned L’Interdit and Abstract Expressionism. Odd choice of fragrance, odd connection. And the lack of fragrances from the middle decades of the century: was this just that MAD could not negotiate with a corporate supplier/sponsor for fragrances the curator might have wanted?

But anyway, the exhibition is a beginning, not an end. No exhibition answers all questions, and in any case, this a temporary show. MAD is doing something new and innovative and if they claim too much or reach too far, it’s understandable.

Annemarie, So true—this is the first of many fragrance-centered projects, at many institutions, I hope. And I’m still thinking about the exhibition, and one more question in my mind is: who was the intended audience? Not someone who has already smelled (and read about) these fragrances and the overall history of perfume in the 20th century, because there isn’t much new information for those people (including many NST readers). But what would a member of the general educated public take away from this exhibition? I’m really not certain…

For people who have never thought about fragrance, it will be impressive, I hope. The idea that a real person – not a brand or corporation – created a perfume, and that it was a creative process, will be new for many people. As will the exercise of trying to match scent with language. This is a big journey for people who never do anything other than give themselves a casual spritz of L’Eau d’Issey before they head out the door.

I really do hope the show will have this effect on its visitors. Then they can read further on the subject of fragrance, place some sample orders, find fragrances that fascinate them, start their own blogs…!

It trikes me, from your description, as odd that so little social context is given. Normally, museums go out of their way to provide information in all kinds of ways of the social and artistic context. American museums nearly always arrange pieces chronologically, and the labels and (often printed texts on walls) provide capsule descriptions providing both biographical and artistic context. In the case of fragrance, the ads and bottle are used by the companies to create a context (even it often seems to be laughably false or cliched for the purchaser to regard the perfume as evoking). So why leave that out?

Also typically, the assignment of a work to some large movement is not usually just the curator’s opinion. Van Gough was a not a post-impressionist because someone at the Met decided he was. Van Gough was post impressionist because his work followed the impressionists in time, and he was clearly influenced by them, but his work represents a change in direction.

In contrast, I suspect that neither Mugler nor the nose for Angel was thinking I will be a Brutalist. They may have been thinking, well this will smell different than the other choices a consumer will have. Channel No. 5 was probably developed to be modern (if not modernist). But what exactly were they thinking of as modernist? Louis Armstrong, the Soviet state, cubism)? Channel fashion was designed to liberating the wearer from heavy, imobilizing clothes which concealed the movement of the body, and the perfume seems less than an applied scent than previous perfumes like Jicky.

Dilana, Thank you for this very thoughtful comment; I completely agree.

I understand that this show had the intention to look at fragrances beyond the marketing apparatus—isn’t that why we all started reading and writing perfume blogs? However, I also learned to study art, literature, etc. within the contexts of the artist’s oeuvre, the artist/client relationship (if the work was a commission), the social/historical background, so on and so forth, and this perspective influences my interest in fragrance.

Maybe the catalogue goes into more detail? I haven’t seen it yet. In any case, this review is limited to the exhibition, which is all most people will have the chance to experience.

After reading Ida’s comments below, I think that perhaps Chandler’s point of view was that there is so much commercial advertising “context” for perfume, that it is necessary experience the scents without that overlay, in order to fully appreciate them as art.

However, doesn’t labelling certain fragrances as brutalists, or romantic, create another context, and one which he created totally outside either the corporate “patrons” (as Chandler has put it) or the nose (artist as Chandler has put it))’s intent.

More to the point, I think the social context is interesting and ultimately advances his theory that perfume is art/

. Why did so many perfumes in the 80’s chose negative names (Poison Obsession, Opium)? Why was the 80’s dominated by big sillage perfumes (my opinon, because people were wearing them to smokey, sweaty, flashy discos and the fragrances, like the wearers trying to hook up, had to shout). Eau D’Issey, as I recall was a subtle rebuke to that loud sillage, so it was made as a new direction from the existing aesthetic.

Why are there so many, cheaply made, celebrity scents right now?

When you think of the perfumers as acting, or reacting to society, AND to the other perfumes out an the market, or following traditions, then isn’t it easier to see the perfumers as artists working in their field and within their time.

The Tresor part sounds very interesting. Just gonna keep the ol’ mouth shut about pretty much everything else.

Speaking from previous experience? 😉

Jessica, thank you for your thoughtful review — flying over from Paris to see the show will not be happening for me, so I was looking forward to reading about it, and you’re definitely qualified to tackle the job! Based on Chandler Burr’s talks and interviews, I’m not surprised by the issues you raise. And having had the opportunity to speak recently with one of the perfumers whose work is featured, I can confirm that he is as puzzled by the label ascribed to him as you are.

I agree with Ari, the Trésor part does sound interesting (after all, the other scents can be discovered in shops, while this is a unique opportunity to discover the mods of a landmark fragrances). And the interactive room is a great idea. Now is there any chance you’ll review the catalogue?

D, Thank you! I’ve just circled back to read your response to the Blake Gopnik interview. We seem to have shared a few of the same concerns over this emerging project.

I haven’t seen the catalogue yet—it’s only available for pre-order right now. Since it’s priced at $250, I doubt I’ll be purchasing a copy. I wish it were available in a non-deluxe, non-coffret version, just a book without the fragrances, so that more people could own it.

This is a wonderful and thorough review and you’ve highlighted the problems and possibilities very well. You know I too am very invested in context and usage. It’s interesting though, how the whole of the show seems to counterbalance, and maybe even overwhelm, the classification framework at its center.

Hello, A!

I’ve been out all day and I’m just about to go over to your site to read your own thoughts on exhibiting/teaching fragrance.

The idea of perfume as the subject of a museum exhibition thrills my soul, of course, but this particular exhibition feels like something of a Pyrrhic victory to me. I suppose it’s just the first of many projects at the MAD, but as the first project, it’s so crucial…

Thanks for the review. I am planning to visit next Saturday and will just enjoy it for what it is. I do not have deep knowledge of the arts nor their history and will be blissfully unaware of what’s missing. The lack of logos and marketing does not bother me one bit.

Hajausuuri, let us know what you think afterwards! I have a feeling you’ve already smelled most of the 12 fragrances in other places, but the Tresor section and the video are interesting for any fragrance obsessive.

Thank you for posting such a thought-provoking review.

And a Lou Reed sighting!

Well, I did really enjoy that moment, I have to say. And although I snapped his photo, I didn’t interrupt his experience of Angel by speaking to him, etc. 🙂

Excellent review, Jessica. Your article and Alyssa’s reinforce my belief that perfume people are hella smart.

And — LOU REED!

(Actually, everything I read on this site and on the other perfume blogs I follow confirms my belief that perfume people are hella smart, but I was trying to stay on topic.)

I was sort of shrieking “LOU REED!” inside, but I managed to stay relatively calm outside. 😉

Keep reading! Keep commenting! We all need these wonderful, multi-directional conversations.

I tell you what, I am pretty sure I enjoyed your review far more than I would have enjoyed the exhibition.

I am definitely a straight-up peasant, plain and simple; plebian in my tastes and thought processes and I frankly Just Don’t Get It. The Emperor apparently still hasn’t found his clothes.

I guess I’m having a hard time working up any kind of enthusiasm for a perfume exhibit that deems Light Blue to be worthy of being displayed in a museum. CK One must have had a prior commitment. (Or a smaller budget?)

I am also too literal minded to be comfortable with sticking my head in what looks like a urinal and inhaling deeply. And those lip-like things spitting out the cards are just gross, to me. I suspect someone in the planning stages was having quite the laugh at imagining people interacting with both of them.

All in all, it’s the kind of high-end, pretentious sort of thing that makes me leary about even wanting to go to NYC. They’d laugh my hillbilly behind right out of town!

Hopefully the next one will be in some Midwestern city, nice and straight forward and easily understood….or somewhere in the South, where I am pretty sure one won’t need to stick ones head in a toilet to enjoy the scents.

hah! Jolie, I know many New Yorkers who would be happy to have you around.

I didn’t always understand the choice of fragrances, but I’m assuming there were some complicated behind-the-scenes issues in dealing with all these corporations. I’ll never grasp the allure of D&G Light Blue, either, but it’s been one of CB’s favorites for a long time, right?

The MAD director has joked about the installation having “pornographic” elements. It *is* odd, especially since the show’s philosophy separates fragrance so entirely from the body.

Well done. I hope the curator(s) involved do read this and take into account that they are playing to a range of audience, and not just preaching to a blank slate awaiting to “receive” wisdom. Still, I applaud the museum for opening up the issue of fragrance at all, and thereby getting the public to focus attention on it. Unfortunately, Tresor is really a hard one for me to enjoy, it reminds me of someone I found very difficult and also gives me a headache. Sorry to hear that the price of the catalog is so crazy. That makes it redolent of the haughty exclusivity perfume is often not so well served by. Plus, you can get a FB of Carnal Flower for that amount.

I’ve enjoyed all my previous visits to the Museum of Arts and Design, and I’m glad they’ve accepted this medium/craft/discipline into their fold. You’re right: that’s the big picture!

I went to this today with my sisters, neither of whom know much about perfume beyond the fact that they don’t like too much of anything.

I actually really liked the design of the exhibit space, but definitely felt the lack of contextual information. The wall text threw around a lot of technical terms, but then didn’t explain them. My sisters ended up saying, “I liked that…. I don’t like that,” without learning what aldehydes or accords are.

I’m hoping that because this is the first exhibit for Burr that he was just trying to get people used to experiencing perfume in a museum setting, instead of creating a wall of impenetrable language about notes and context. It’s like he was introducing perfume as a sort of modern art, in a white cube gallery and the intention is for the viewer/sniffer to decide the meaning on their own.

I agree, I think the goal here was to establish perfume = art in a cool rather than stuffy way. The fact that the exhibit attracted an icon like Lou Reed suggests that may be working.

Cloudy, I agree that the technical terms don’t mean much without *some* kind of definition/information attached. But I’m glad you and your sisters found other aspects of the show to enjoy…

Jessica, thanks very much for this review and the photos. And the LOU REED sighting!!!!

It seems to me that CB has two goals that are working a bit at cross purposes a bit. His Untitled Series on Open Sky is adamantly about experiencing perfume as olfactory works of art completely detached from the advertising imagery and any other context (except for his own descriptions, curiously). Here, he seems to be trying to establish perfume as Art by linking it to visual art and architecture trends – and still trying to delink them from their own visual component and context. On one level I think it’s worth a try; on another level, I would probably also miss Angel’s bottle.

By the way, there was an interesting spot on NPR Studio 360 this afternoon about researchers studying how musical sounds can change the way food tastes (which makes me wonder if one can fully experience Gucci Rush outside of a dance club). Maybe Angel’s bottle and advertising should have been the next room in the exhibit, and visitors could see if Angel smells different in that context?

Noz, I accidentally overlooked your comment last night, but now that I’m reading it: yes, and yes, and yes!

Hi All,

I am thrilled that the exhibition happened at all, and to some extent, I feel unqualified to comment on it and on the review, because I haven’t seen/experienced it. But I DO feel the urge to comment:

Consider that THIS conversation and other musings about the context/lack of it may have been precisely what the exhibition aimed at. It is interactive after all, and interactivity means also the conversations that continue beyond the moments encapsulated in those spare walls. It strikes me as highly appropriate that works of which we know the context so well are on display for the nose – without context. It makes us think about how and if Angel would work without the added charm of the star bottle. By removing context, Burr makes us consider what role context plays in our appreciation. This strikes me as highly appropriate for an art form, in which many users do NOT know the context. Some perfume wearers do not know/care for the context of what they are wearing – thus the sometimes odd smell/sight combinations one would experience. And people on the street, who are recipients of the smells others impose on them, ALSO often do not know the context – yet they experience the smell. Someone may say or think: that perfume smells divine. It could be Jicky, and they wouldn’t have the foggiest. The same is true for all art forms. Perhaps pre TV/pre internet villagers in the South of China may not know any of the context of the Mona Lisa when they first see it. What makes that interaction (and this exhibition) interesting, is to ponder what role innate value plays (and what role context) in the connoisseur’s interpretation – as well as the non-connoisseurs. So I want to say: well done Chandler Burr, and lo! we are doing what the exhibition intended us to do: give thought to the value of context.

You make an excellent point – that the exhibition asks us what role innate values have, and what role context. (I wonder if that is quite what Burr intended though?)

This reminds me a bit of the decanted perfume that I suppose many of us buy from the the commercial decanting services or via splits. I have a row of small identical bottles on my dressing table and yes, the anonymous bottle does detract from my pleasure a little.

The anonymous bottles / vials annoy me too only because if I love the juice, I would have no idea what it is in order to satisfy my FB fix 😉

I’m wondering whether that was the curatorial intent, too. I like the idea; I’m just not sure that’s what’s going on here!

And yet, if one were to sniff the neck of that wearer of Jicky and exclaim, “that perfume smells divine and like lavender and citrus with a heaping dose of civet” Chandler would overhear the remark and have a coronary or possibly strike you. No, one must adhere to some abstract experience of fragrance or one can go jump in a lake.

hah!!

I wrote something similar to this in the comments on Alyssa’s post on her blog, but part of what bothers me about stripping the perfumes of their packaging and context is that by doing so, Burr pretends he has “decommercialized” the perfumes so that we may appreciate them as art, rather than as products. However, the very fact that the sponsors of the exhibit are the fragrance houses that produce the perfumes makes it clear that in a way this exhibit, and Burr’s Department of Olfactory Art, is a marketing opportunity as well. Not to say that it invalidates these perfumes as art – maybe they’re art AND a product. But, I wonder, will Burr ever be able to include perfumes made by independent or artisanal perfumers in his future exhibits? Or is the money behind it just not going to work? I mean obviously to prep this exhibit, the fragrance houses had to provide liter after liter of these perfumes. Could an independent operation do the same?

I say that, and I actually enjoy and appreciate the vast majority of perfumes in this exhibit. So I’m not questioning that Burr chose poor perfumes, and I think it’s fine for him in this inaugural exhibit to have chosen more well-known, big-name perfumes. But I wonder what the future will hold.

Another point, about the exhibit. I used to read this blog called Sociological Images. I don’t read it very much anymore – but I feel like they would have a heyday analyzing the exhibit. They specialize in rooting out the hidden social messages, particularly gender messages, in visual imagery – often commercial imagery but not always. To be honest, more than anything else, what I find discomfiting about this exhibit is the admitted “pornographic” nature of the exhibit – obviously MAD knew that these installations resembled female anatomy and went on with the exhibit as is. Why have such titillating suggestions of the female body and not address anything cultural about the perfume, the fact that women are the primary consumers of perfume, that perfume is generally worn on women’s bodies, and that perfume is marketed to us as if we are basically bitches in constant heat? Sorry for the strong language, but I find it somewhat troubling that Chandler Burr, a man, chose to present the exhibit in this way without any apparent confrontation of the multitude of gender issues inherent in perfume’s creation and marketing. I am not really easily offended and wouldn’t even mind the installations had there been any discussion of perfume beyond the high-minded arty discussion that shoehorns perfume into visual art categories. So the problem isn’t the installations, but the installations combined with the lack of thoughtfulness around the category of gender.

Good points. About the funds donated by big companies: they’re not just donating the juices, they are financing the exhibition itself. That’s more than any independent house would be able to supply.

About gender issues, I’m not sure the female character of the design wasn’t the curator’s blind spot. I’d take your argument further though. By imposing the vocabulary of fine arts (perfumers are “olfactory artists”, perfumes are “pieces” and “lent by” labs or brands), the exhibition *is* applying covert gender politics by “ennobling” something that is perceive by most as futile, linked to fashion and seduction, and therefore feminine. In this context, the “lady bits” in the design could be thought of as a return of the repressed, don’t you think?

I’m wondering about the collaborative relationship between the curator and the design firm and the museum’s adminstration… *someone* along the way must have pointed out the anatomical nature of these installation features, right? I’d think so! but I have no way of knowing whether such a conversation occurred.

BG, I really appreciate your points about the “commercial” aspect of fragrance and how it’s present and/or absent in this installation.

The non-role of the female body in this exhibition hit me more on my second visit, when I watched (female) visitors in the interactive gallery sniffing the fragrances displayed in bowls. Occasionally a woman would dab her own neck or wrist with a freshly dipped blotter if she really liked the fragrance she’d just smelled. The main gallery almost makes us forget that fragrance is supposed to be smelled on skin, not in sterile jets of air that are somehow whisked back into their diffusers as soon as we’ve inhaled them.

And yes, some of the featured perfumers are female, but in addition to the female customers/wearers, female designers like Coco Chanel or Miuccia Prada are not even mentioned, although their aesthetics are essential to the brands that made these fragrances possible.

Alyssa made some excellent points about gender and perfume-as-art in her own recent post:

http://www.alyssaharad.com/scent/perfume-is-not-an-object-a-few-thoughts-about-perfume-and-art

Jessica,

My head is spinning! I’ve read your post, went over to GdM, and then off to Alyssa’s blog, read the comments at all three, and also popped over somewhere, I don’t know where, to read the Gopnik article!

Wow, where have I been?!?

I have so much to say and can’t get it out. But I will say this, fantastic article Jessica! I loved every bit of it.

I will also say this, I am so glad Gopnik called Burr out with this quote, “Burr, self-taught in aesthetic theory, seems to have conflated the artifice found in art with a chemist’s idea of the artificial, and now he won’t let go of that conflation.”

He summed up what I have been feeling for years now. Just let the conflation go already! It won’t hurt, really, it won’t 🙂

It’s a favorite topic right now, apparently! and there were a few preview posts, but the discussion really only took off then she show opened, so don’t worry about missing much! 🙂

I think this is one of the best pieces of fragrance journalism I have ever read, I hope you’ll enter it for an award.

Clear and balanced, descriptive and erudite, informing and entertaining, thanks for being our eyes and ears Jessica.

GSD, Thank you for these very kind words. I’ve just re-read my review, and I still stand by it. I’ve been disappointed by most of the exhibition’s press coverage so far, since it just tends to repeat the same few ideas from the press release, some of them not entirely accurate.

However, I don’t think I’ll be rewarded for taking a not-wholly-positive stance toward a fragrance-related event. The industry doesn’t seem to work that way…

Thanks again!